By Bill Ivey

In 1901, 155 frustrated, angry elite white males met to create Alabama’s 6th constitution. They built a horrible document that consolidated power at the top and cheated everyone else–then and now.

And, worst of all, the only reason it passed was due to massive voter fraud in Alabama’s Black Belt.

These days we often hear cries about voter fraud. However, according to a Brennan Center Justice review of more than a dozen studies, voter fraud in the U.S. is exceedingly rare. So, at all levels of government, the notion is pretty much a myth in the last century or so.

The greatest, most dramatic voter fraud incident I know of is this one. Once again, Alabama is infamous for something terrible: The longest, worst state constitution in the U.S. And, well over a century later, it negatively affects us in ways we don’t realize. I hope to shed some light on the horror that remains the foundation of our state government.

Our 1901 Constitution is a racist document and we should get rid of it for that reason alone. However, it is also designed to keep power and wealth in the hands of a few individuals and organizations–and to hell with everyone else, including most of Alabama’s whites.

It’s fascinating and ironic that Alabama’s Black Belt provided such a huge “pivot point” in Alabama’s history. That region was made up of the once-rich plantation counties. Each county was made up of small minorities of powerful whites and huge majorities of former slaves.

As you will see, outside of 12 Black Belt counties, the Constitution was rejected by a small margin statewide. But it passed overwhelmingly in those predominantly black counties. As Ron Casey, my all-time favorite Birmingham News columnist, asked in 1999, “Is it more reasonable to believe that blacks voluntarily voted to disfranchise [sic] themselves, or to believe that ballot boxes were stuffed like Christmas geese?” We’ll examine those voting results shortly.

In 1865, Reconstruction continued a very rough period for Alabama. Scarred by defeat, the Confederate states were the only region in the country to have been defeated in a war. Alabama suffered tremendous casualties–about 60,000 men killed or seriously wounded–and the 435,000 slaves (45% of the state’s population) who had been the foundation of Alabama’s economy were free. And Alabama was occupied by Union troops from 1865 to 1874.

Alabama was required to pass a new constitution in 1865 in order to rejoin the Union, but the one passed by the state’s elites was so racist it was rejected by the U.S. Congress. So, until Alabama ratified a more progressive document in 1868, it was run by a military governor appointed by Congress.

As one would expect, Republicans controlled the constitutional convention that began in late 1867. Of the 100 delegates, about 80% were white (“Unionists” who’d not supported the War) and the rest were black. Their primary goals were 1) equality before the law, and 2) a public school system that would be available to both blacks and whites.

According to the Encyclopedia of Alabama, Alabama’s white majority rejected the new constitution outright and most of them boycotted the ratification vote in February 1868. Because the U.S. Congress required majority participation, ratification failed. Congress responded by eliminating that provision and readmitted Alabama to the Union.

Let’s fast-forward through the events that preceded the fateful 1901 Convention.

Still controlling Alabama politics, in 1868 Congress appointed William Hugh Smith, a Unionist Republican, as governor and, because of a Democrat boycott, Republicans filled most state offices. As you can imagine, Alabama’s elite white Democrats were frustrated and outraged. In his two-year stint, however, Smith did little to suppress the terror unleashed by the Klan (particularly in the Black Belt) or to restrain the traditional power-brokers. He was defeated in the election of 1870 by Democrat Robert Lindsay.

In 1874, after almost a decade of Republican rule, ex-Confederate Democrats, in an election marked by fraud, intimidation, and violence, swept the elections to regain control of the state’s legislative and executive branches. Newly elected governor George S. Houston and his fellow Democrats were part of a political coalition known as “Bourbons,” and they consisted primarily of a corrupt alliance between the Black Belt planters and the “Big Mules,” the increasingly influential group of capitalists who had quickly risen to power in Birmingham. (The term Bourbon originated during the Reconstruction Era and was used by the Radical Republicans to label their Democratic opponents as anti-progressive and ultraconservative.)

The Bourbons sought to restore pre-War/Reconstruction white supremacy, limit the size of government, centralize power in Montgomery, decrease the political power of African Americans, and create a “New South” in which business and industry would flourish. They resorted to race-baiting by urging white Alabamians to put aside their class differences and “redeem” the state from the racially integrated Republican Party.

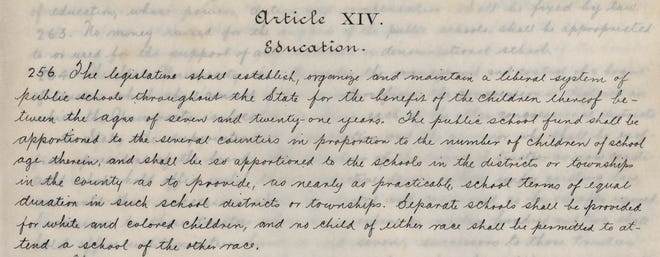

Their immediate goal was to get a new constitution ratified. 99 delegates assembled in 1875 (80 white Democrats, 12 Republicans (4 who were black), and 7 independents). They created a document designed to reduce the size of the state government and the services it provided, lower taxes, and constrain the political power of blacks. They established segregated schools, abolished the state Board of Education, shifted the Legislature to biennial sessions, and limited taxation powers for local governments. They reduced funds for public education and state services. However, still fearful of Federal enforcement of the 15th Amendment, the delegates didn’t go as far as they would have liked–so the 1875 Constitution did little to alter voting rights.

A quarter-century later, Alabama’s white elites remained dissatisfied with the 1875 Constitution. They were outraged by the chaos and severe conditions previously imposed by Union Reconstructionists. Bourbons were harsh, selfish, fearful, and fiercely determined to completely consolidate power at the top.

By 1901, there was no more fear of Federal intervention in Alabama, so the Bourbons focused on disenfranchising blacks and poor whites. Populism (poor farmers and pro-union workers) and an early form of black power, which had exploded throughout the South in the 1890s, had to be stopped.

It would not be that difficult to disenfranchise blacks, but the Bourbons also had to build structures to do the same to poor whites. They could not afford the chance that a new Populist-black alliance could emerge. The most serious challenge was how to render poor whites powerless, yet convince them to vote yes for ratification.

Meanwhile, during Reconstruction, the South’s only industrial-based city, Birmingham, had been born, and by 1901 was thriving. Founded in 1871, Birmingham was the fastest-growing city in the South. By 1900, Birmingham’s 140,000 residents made up almost 65% of the state’s urban population. This outlier city was controlled by big industrialists, staunch capitalists, and bankers known as “Big Mules.” And they had built the city with cheap (almost slave) labor.

Through an exclusive contract, Birmingham’s Tennessee Coal and Iron Company (TCI) employed thousands of convicts leased from the state. By 1898, nearly 73% of Alabama state revenues came from convict leasing. Now the Big Mules and the rich whites from the Black Belt had something in common–consolidating power at the top. This explains why Birmingham’s Big Mules formed a Montgomery-based unholy alliance with the old-time Black Belt planters and became part of the Bourbon coalition.

In early 1901, Alabama’s legislature approved a statewide referendum calling for a constitutional convention. On April 23 the referendum passed with the aid of massive electoral fraud (more on that shortly) in the Black Belt. In May, 155 delegates assembled and elected Anniston delegate John Knox president. The delegates were mostly Bourbons: lawyers, politicians, planters, and businessmen. All white.

Convention leaders believed that disenfranchising blacks would be legitimate if it was done on the basis of their “intellectual and moral condition,” and not because of their race. Additionally, in his opening address, Knox made it clear that the main purpose of the convention was “to establish white supremacy in this State.”

According to state historian Harvey Jackson, Bourbons were terrified by the rising populist tide of the time, especially the advances enjoyed by blacks. They were determined to maintain control over their greatest assets: low taxes and a cheap, compliant workforce.

Knox and other Bourbon leaders aimed to establish white supremacy through “legal means,” not by “force or fraud.” Knox claimed this was justified by declaring the moral and intellectual inferiority of blacks; a pretense that race was not at the heart of the matter. It’s ironic that the Bourbons used the term “legal means” since they eventually chose to steal votes in order to get the Constitution passed.

The new Constitution included strict suffrage requirements (the Federal government requirements were: male, age 21). Alabama required literacy tests, employment for at least a year, and stringent property qualifications.

Individuals could also be disenfranchised for one of the following subjective “shortcomings”: 1) Being convicted of a simple misdemeanor such as “vagrancy;” 2) Being alleged to have moral failings or mental deficiencies.

Bourbons, however, couldn’t afford to lose the poor white/populist votes, so they executed a classic bait-and-switch maneuver. They passed a series of “grandfather clauses” that led most poor white males to believe they’d be able to vote, and then they added a requirement that all voters ages 21-45 had to pay a cumulative poll tax of $1.50 each year. Most poor whites existed in a barter economy and would never be able to afford to vote. By 1941, 600,000 whites and 520,000 blacks were disenfranchised–and there were only 444,000 registered voters in the entire state.

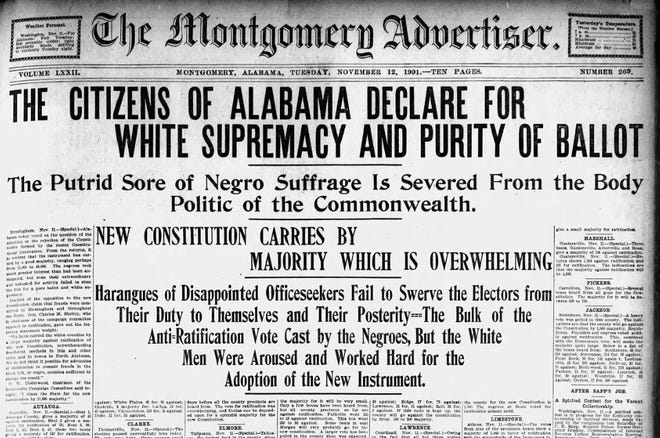

The Bourbons, who campaigned openly on a platform of white supremacy and honest elections, stole the election. They did so in Alabama’s Black Belt, long the site of voter fraud, by “voting the Negro,” to use the terminology of the time. Here’s the quick story of that mess, which is one of the most consequential voter fraud incidents in U.S. history.

The 12 Black Belt counties, where black voters far outnumbered white voters, reported about 36,000 “yes” votes and 5,500 “no” votes–a margin of approximately 30,500 in favor. The statewide margin of victory was about 27,000. The other 54 counties of the state voted against the constitution: 76,000 to 72,000 (rounded)–a margin of about 4000.

In Dallas, Hale, and Wilcox counties alone, 17,475 votes were cast for the constitution and only 508 against it–all the more remarkable because the total white-male voting population of those counties was 5,623. (Jackson) McMillan also notes a report (Mobile Register, November 13, 1901) that the Black Belt counties were slow in reporting their votes—an old tactic by which Black Belt political bosses could determine how many votes they “needed” to count. Thus on the face of the official returns, we are expected to believe that a considerable majority of African American voters voted to disfranchise [sic] themselves. (Source: McMillan)

From the Alabama Law Review: “Such tactics included ballot box stuffing; theft of ballot boxes; removal of polls to unknown places; burning ballots before elections; illegal arrests on election day; importation of voters who did not live in the precinct; calling off names wrongly; fabricating reasons to refuse to hold elections in precincts populated with blacks; the voting of dead or fictitious persons; ensuring that poll watchers and ballot counters became drunk while votes were counted; and, organizing “disorderly demonstrations” to intimidate voters.

Dr. Harvey Jackson: “Through violence, appeals to white supremacy, and massive voter fraud, the Black Belt’s oligarchs had defeated the 1890s challenge of the Populists and inscribed their power in a straitjacket of a state constitution that disenfranchised the African American population along with many poor whites. The Bourbons stole the election and just about everybody knew it. But there was nothing the anti-ratificationists could do; no appeal they could make. The Bourbon Democrats had won, and in winning, they had created a system that would protect their power and property. What the delegates produced was more like a code of laws than a constitution, and the effect was to prevent change rather than promote it. But that was what the Bourbons wanted.”

“This 1901 Alabama constitution,” concluded historian Wayne Flynt, would keep Alabama “throughout the Twentieth Century at or near the bottom among all states in . . . property taxes, public services, and quality of life.”

The U.S. Constitution, an international model, is a few pages long and has only been amended 17 times since the Bill of Rights (1st 10) was passed in 1791–almost 230 years ago. It describes the principles and philosophy of federalism, establishes the basic structure of a three-branch system, and generally lays out the division of power between the federal and state governments. It also provides maximum flexibility through what is known as the elastic (“necessary and proper”) clause.

Alabama’s illegitimate constitution, however, is an embarrassment. It has been amended 946 times in 120 years, it’s the longest constitution in the world, and it’s considered the worst one in the country. According to the Public Affairs Research Council (PARCA):

- While the constitution may have started by laying out general statewide principles, its accumulation of amendments is due to the exceptions to those principles and special cases made for specific localities.

- Approximately 70 percent of the amendments are local in nature.

- The framers of the Alabama Constitution of 1901 wanted to set limits on government…they wanted strict limitations on what local governments could do, so they set up a system in which many local decisions have to flow through the state government for approval.

- The local amendments to the constitution are only the top layer of complexity: The state legislature has passed over 36,000 local laws applying to specific counties or municipalities. This heavy involvement of state legislators in local affairs:

- Tends to create confusion about who is responsible for decision-making.

- Blurs the lines of accountability when things go wrong.

- Interferes with the development of a culture of statewide planning and policymaking.

There’s more, so much more. As I stated earlier, with the exception of a certain small group of elites in Alabama, we ALL continue to be negatively impacted by this horrible and illicit document.

We have the most regressive tax system in the country. Our poorest 20% pay more than twice the real tax rate (all taxes combined) than our richest 20%. Huge landowners, now mostly outside corporations, continue to pay minuscule taxes per acre–the lowest taxes in the nation on farming, timber, and mineral-rights land. Property taxes are the most stable of all taxes; if we doubled our property tax rate tomorrow, we would still have the lowest rate in the nation.

As mentioned in the PARCA section, the lack of home rule is strangling us all. Our “founders” made sure that most everything of importance would have to make its way through Montgomery.

- State legislators spend an inordinate amount of time on the “micro” (local) issues, at the expense of “macro” (state) issues. In some rural areas, one state senator may have control over several county commissions.

- Legislators are powerful, and–without a new constitution–are not about to let go. Bills that would allow ordinary citizens (through initiative/referendum) have never made it through the “system.”

- In reality, the people of Alabama don’t run the state. And, because the legislators are so powerful, they’re often controlled by special interest groups. This is nuts: We have 35 state senators and 105 House members. There are approximately 600 registered lobbyists in Montgomery, 17 for every senator and 6 for every House member. When the legislature is in session, it must be quite a spectacle.

- According to PARCA, 93% of Alabama’s revenues are earmarked. The national average is 24%. Lawmakers can’t shift sizable amounts of revenue to where they’re needed most. Consequences? Slow economic growth and limited services.

In a 2019 Comeback Town Guest Blog, Bruce Ely eloquently laid out just ONE frustration of trying to conduct business in this Alice-in-Wonderland environment: “Alabama is considered to be one of the worst three, if not THE worst, state in the U.S. when it comes to red tape in sales tax compliance. That’s primarily because we’re the only state that allows each and every city and county to impose and collect its own sales, use and rental taxes… Audit horror stories abound.”

Largely because of this infamously deplorable Constitution, our state functions much like a Third-World region. Here are a few of those third-world-type characteristics.

- Alabama’s economic system is an exploitative one–characterized by outside ownership, profits flowing out of the region, and exploitation of natural resources (such as timber, mining, paper, chemicals, and steel). The state is heavily dependent on outside capital for its development. Regions Bank is the only Fortune 500 Company headquartered in Alabama. The best example of our dependence on outside capital is the automobile industry. Here’s a scary thought: These huge multinational companies, just like the old textile mills in Alabama, are inherently connected to the fluctuations of the world economy. Should it dramatically change (electric vehicles, self-driving cars, decline in total demand due to COVID, etc.), companies like Mercedes wouldn’t hesitate to walk away from their Alabama facilities.

- Our state government is weak, but just strong enough to maintain the status quo. The best example I can think of is this: In a state with exceptional natural resources, we’ve historically allowed large companies to pollute our air, water, and soil. Alabama’s Department of Environmental Management is virtually toothless. Google these types of issues and prepare to be sickened…

- Alabama is severely limited by its suppressed and undereducated underclass, which is characterized by malnutrition, poor health in general, high infant mortality rates (in some locations, it’s worse than many third-world countries), and a lack of access to dependable transportation.

- Like most third-world regions, our labor sector is weak. Alabama’s labor force is characterized by limited union influence, low skill and/or education levels, and poor health.

As citizens of Alabama, will we ever unite and fight for a better future? I believe that Dr. Flynt is the greatest historian this state has produced. For years, he has maintained that the reason we’ve never had a populist revolt in Alabama is that the elite whites have consistently driven a wedge between poor whites and poor blacks by convincing the whites that their biggest threat is the (remove) “the” to just say poor blacks) poor blacks. The truth is that those elite whites are the threat to the rest of us.

With the exception of then-Chief Justice Howell Heflin’s revision of our judicial branch in the 1970s, Alabama has NEVER done the right thing. The Federal government, primarily through court decisions, has always had to make our leaders shut up and do what they should’ve done in the first place. (A story for another day…)

Will we ever do the right thing? This constitution needs to be thrown out and become a relic of our tainted past. We can’t depend on the state legislature to make changes; as a matter of fact, it would be dangerous to leave this massive job up to them.

Check out the Alabama Citizens for Constitutional Reform site https://www.constitutionalreform.org. Organized by Dr. Bailey Thomson and Dr. Tom Corts in 2000, their goal is to have a citizens’ constitutional convention to rewrite the entire Constitution. This is desperately needed.

Our 1901 Constitution is a massive fraud that’s lasted more than a century. We’ve beaten our collective heads against the wall long enough. It’s time to control our own destiny. Otherwise, Alabama will continue to be doomed to a fate worse than mediocrity.

On November 3rd, Amendment #4, if approved, allows recompilation and removal of racist language from our State Constitution. This isn’t adequate, but it’s a start.

Resources

- Project Vote: “The Politics of Voter Fraud”

- Alabama: The History of Deep South State(Rogers, Ward, Atkins, and Flynt), 1994.

- Constitutional Development in Alabama. Malcolm C. McMillan, Chapel Hill, NC: James Sprunt Studies, 1955. (The definitive source on this subject.)

- “1901 Constitution fraudulent, ‘criminal,’ and ours.” Bob Blaylock, The Birmingham News. (2011; updated 2019)

- “Alabama’s 1901 Constitution: Instrument of Power.” Alabama School of Law, 12/9/16.

- “The Rat in Ratification,” The Birmingham News 11/10/07.

- Wikipedia/Wikiwand History of Alabama

- “A New Century, A New Constitution,” Birmingham News Series, (Jan.-Feb. 2001).

- “The Burden of Fraud on Alabama’s Legacy,” The Alabama Law Review, 5/4/14.

- The Nation’s Longest Constitution Just Got Longer, PARCA (Public Affairs Research Council of AL), 12/10/14.

- One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866-1928.Matthew J. Mancini. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1996.

- Bergengruen and Villa, “Homegrown Threat,” 9/21-28, 2020 Time Magazine.

- Alabama Citizens for Constitutional Reform

Bill Ivey is a retired coach and History/Government/Economics teacher who has a BS in Business from the University of Alabama and a Master’s degree in History from UAB. He recently closed his Birmingham Basketball Academy (due to the pandemic) and is now fully retired after 45 years of working with young people. He and his wife Cathy founded the Carolyn Pitts Class for Social Justice (Sunday School) at First United Methodist Church downtown, which has continued to meet virtually since March.