Link to a 2001 video of Wayne Flynt and Anne Permaloff being interviewed by Bailey Thomson about the 1901 Alabama Constitution and the attempts to reform it that were blocked by the “Big Mules”.

https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/lib_ac_alhist/12/

Link to a 2001 video of Wayne Flynt and Anne Permaloff being interviewed by Bailey Thomson about the 1901 Alabama Constitution and the attempts to reform it that were blocked by the “Big Mules”.

https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/lib_ac_alhist/12/

Alabama’s 1901 Constitution was aimed at keeping blacks and poor whites from voting and achieved the framers’ intent.

Alabama voters will have a chance to ratify a recompiled state constitution when they go to the polls for the general election on Nov. 8.

The Alabama Constitution of 2022 is a reorganized version of the current constitution, which has been the state’s foundational law since it was ratified in 1901.

The 1901 Constitution has grown to be almost indecipherable after more than a century of piling on amendments. Original sections that were changed and repealed remain in the document. Amendments that were changed by later amendments remain. More than 700 amendments apply to only one county but are mixed with the statewide amendments.

The Constitution of 2022 is the product of an effort to arrange the massive document in a coherent format. It folds the amendments into the main articles. It organizes the local amendments by county, municipality, and topic.

The vote in November will be the culmination of a project that started a few years ago and was built on decades of reform efforts.

Legislative Services Agency Director Othni Lathram, who has overseen the drafting of the Constitution of 2022 with help from an advisory committee and the LSA staff, said the main goal is to make Alabama’s foundational law understandable.

Voter-approved process

While the project came in response to the glut of amendments, it took an amendment to make it possible.

In 2019, state lawmakers passed a bill by Rep. Merika Coleman, D-Pleasant Grove, proposing a recompilation of the 1901 Constitution. The bill limited changes to four categories: Remove racist language; delete duplicative and repealed sections; consolidate economic development provisions; and arrange local amendments by county.

In 2020, voters, by a 2-to-1 margin, approved Coleman’s bill as Amendment 951. The amendment directs the head of the Legislative Services Agency, which drafts bills for lawmakers, to develop the draft of the recompiled Constitution.

In 2021, lawmakers passed a bill to create a 10-member committee to assist the LSA and to receive ideas from the public. Six lawmakers and four others served on the committee, which Coleman chaired. They held a series of public meetings starting in July 2021.

Lathram said the LSA and the committee relied on a key resource, a recompilation authorized by legislation that passed in 2003. That project was never intended to be ratified by voters and did not include all the components of the 2022 recompilation. But Lathram said it was an important interim step and the committee adopted it as the baseline for their work.

The final product, the Alabama Constitution of 2022, went to the Legislature during this year’s regular session. Legislators approved it without a dissenting vote, a step required to put it on the ballot in November.

“We spent two years working on these drafts in a very public process,” Lathram said. “There were numerous public meetings, opportunity for the public to engage and participate. When we were done with that process it had to pass both legislative bodies again by a three-fifths vote. They were debated, talked about during the legislative process. Then, of course, it’s got to be ratified in November.

“So, we’re not talking about a quick or simple process. It really was a process with multiple, pretty significant hurdles that had to be checked through the representative government process.”

You can see the proposed Alabama Constitution of 2022 and documents explaining the committee’s work under the Legislative Service Agency’s tab on the Legislature’s website.

Taxes, home rule, and gambling

For decades, advocates for reforming Alabama’s Constitution of 1901 have cited the need to change limits on property taxes that limit school funding and for giving county governments more authority, or home rule.

The Alabama Constitution of 2022 is not that version of reform.

“This doesn’t address any of that,” Lathram said. “It maintains the status quo on all tax issues. It maintains the status quo on all local governance issues.”

The prohibition on gambling in the Constitution of 1901 is unchanged. That means the Legislature cannot create a lottery unless voters approve a constitutional amendment. The Constitution of 2022 does not change the Legislature’s powers in any area, Lathram said.

“It does not take away or give any authority, even on the provisions where theoretically authority is coming out, like on segregated schools or poll taxes, those are authorities that have been taken away under federal case law for over a generation now anyway.

“We are not taking out anything that’s operative. We’re taking out vestiges of a prior time.”

Even though the recompilation does not address some issues that have long been cited as the reasons for overhauling the constitution, longtime supporters of reform say it is an important step.

Kristi Thomson is a retired teacher and principal who chairs Alabama Citizens for Constitutional Reform, which has spearheaded efforts for more than two decades. Thomson said her husband, journalist and educator Bailey Thomson, who died in 2003, would have endorsed the work, including the removal of racist language. Thomson was a founder of ACCR in 2000.

“My husband started his research way back in 1998 and realized that the constitution was just keeping Alabama back,” Thomson said. “And Bailey was an Alabama boy. He grew up in Aliceville. His dream was that over time we could get a new constitution. But we realized that if that was not in the cards could we get reform. And when I say we, I mean the people who support the ACCR mission.”

Thomson said she sat attended the advisory committee meetings.

“I was very impressed with all the research that had gone on and the considerations, the concerns,” Thomson said. “They were so careful in planning how everything would be worded and how it would affect the state.”

Removing racist provisions

An example of how the recompilation works is the treatment of the ban on interracial marriage that is part of the 1901 Constitution.

Section 102 of the 1901 Constitution says: “The legislature shall never pass any law to authorize or legalize any marriage between any white person and a negro, or descendant of a negro.”

Alabama’s ban, like those in other states, was nullified in 1967 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled those laws were unconstitutional.

In 2000, Alabama voters approved Amendment 667 to formally repeal the inoperative ban by a vote of 59 percent to 41 percent.

The Alabama Constitution of 2022 does not have the original ban in Section 102 or the amendment that repealed it. Sections that voters have repealed, along with the amendments that repealed those sections, are not part of the recompiled constitution.

The LSA and advisory committee identified three sections with racist connotations that would not be eliminated by recompilation. Those are removed or revised.

Section 32

Section 32 is the prohibition against slavery in the 1901 Constitution: “That no form of slavery shall exist in this state; and there shall not be any involuntary servitude, otherwise than for the punishment of crime, of which the party shall have been duly convicted.”

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, Alabama abused the practice of involuntary servitude. The notorious convict-lease system targeted former slaves and their descendants for dangerous work in coal mines and other places until the 1920s.

The Constitution of 2022 deletes the last portion of Section 32 and reads: “That no form of slavery shall exist in this state; and there shall not be any involuntary servitude.”

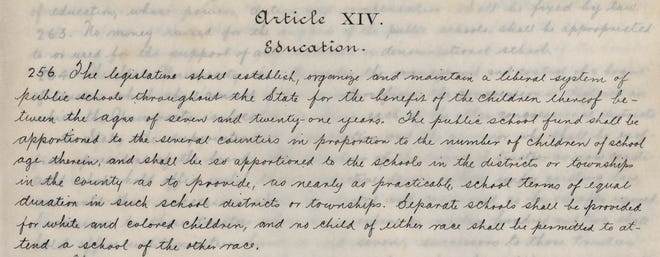

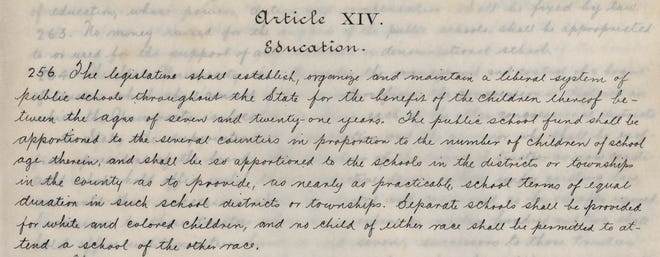

Section 256

Section 256 in the Constitution of 1901 required “separate schools for white and colored children.”

After the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling outlawed segregated schools in 1954, Alabama amended Section 256 (Amendment 111 in 1956) but tried to keep the door open for segregation. The amended version of Section 256 says, in part, “The legislature may authorize the parents or guardians of minors, who desire that such minors shall attend schools provided for their own race, to make election to that end.”

The Constitution of 2022 deletes that portion of Section 256 as well as the original section that mandated segregated schools. Also deleted was a provision from the 1956 amendment that said the Legislature could “require or impose conditions or procedures deemed necessary to the preservation of peace and order.”

Section 259

The poll tax was used for decades to keep poor people, white and Black, from voting. Alabama was one of five states that still had a poll tax when Congress passed a law to ban poll taxes in 1962. That law was ratified as the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1964.

Most of the references to the poll tax in the Alabama Constitution of 1901 are in Article VIII on suffrage and elections. Article VIII was repealed and replaced in 1996, one of several article-by-article reform efforts.

Section 259 is part of Article XIV on education and is the surviving reference to the poll tax. It says: “All poll taxes collected in this state shall be applied to the support and furtherance of education in the respective counties where collected.”

That is deleted from the Constitution of 2022.

Local amendments

The Constitution of 1901 limited the authority of county governments, forcing them to seek approval from state legislators and voters on mundane matters and basic operations. That is why about three-fourths of the 977 amendments affect just one county.

Here’s a few of the hundreds of examples: Amendment 710 imposes fees in drug cases in Escambia County to help fund the canine unit for the sheriff’s office; Amendment 934 authorizes the Madison County Commission to enact noise ordinances; Amendment 938 concerns the use of golf carts on public roads in Marengo County; and Amendment 974 prohibits the use of septic tank discharges as fertilizer in Talladega County.

All amendments, local and statewide, are listed in chronological order in the Constitution of 1901. The Constitution of 2022 moves all the county amendments into a separate volume organized by county and topic.

“This goes a long way toward hopefully that ease of use for voters to allow them to know what laws are in the constitution for their county that don’t exist for the rest of the state,” Lathram said. “I think it’s a very significant portion of the effort.”

History of reform efforts

Governors, legislators, and citizen groups have pushed for constitutional reform for decades.

Gov. Albert Brewer advocated for reform, as did Gov. Fob James during his first term from 1979-1983.

The Legislature passed a new constitution in 1983 sending it to the voters for ratification. But the Alabama Supreme Court removed it from the ballot, ruling that a wholesale rewrite of the constitution required a constitutional convention.

Reformers then tried a different approach, overhauling the constitution article-by-article. One such effort predated the Supreme Court ruling. In 1973, voters ratified Amendment 328, a rewrite of Article VI, the judicial article, authored by then-Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Howell Heflin.

In 1996, voters ratified a new Article VIII, suffrage and elections. That was an effort spearheaded by Rep. Jack Venable of Tallassee.

Brewer chaired a constitutional revision commission created by the Legislature in 2011. It rewrote the articles on the distribution of powers, impeachment, corporations, and banking. All were ratified from 2014 to 2016.

Also in 2016, voters approved an amendment that was a step toward more home rule for counties. It allowed county commissions to adopt policies on county personnel, litter control, public transportation, traffic safety and emergency assistance without approval of the Legislature.

Another amendment approved in 2016 changed the procedure for determining whether constitutional amendments affecting only one county go on the ballot statewide or only in the affected county, an effort to confine more of those votes to the affected county.

Stayed within guidelines

Sen. Sam Givhan, R-Huntsville, a lawyer who served on the advisory committee for the Constitution of 2022, said the panel was careful to limit changes to the four categories authorized by voters two years ago. He said that should give voters confidence in the finished product.

“I would just remind them that they did vote to authorize this before,” Givhan said. “And they gave us very confined parameters with which we could operate to reorganize the constitution and to remove the racist language. And lots of different groups were represented with varied interests to keep an eye out if you will to make sure that we stayed within those parameters.

“There was really no controversy in how we handled it because there were some clear-cut areas that were overt racist language that were removed. There were some that had deep racist connotations that were removed. But there’s nothing in terms of how our government works, how our tax system, nothing like that was changed. We didn’t have the authority to change it.”

Since it was written in 1901, the current Alabama Constitution has been amended almost 1000 times, making it by far the world’s longest constitution. The amendments have also riddled the Constitution with redundancies, creating a maze of words known to befuddle even legal scholars. In addition, Alabama’s Constitution is peppered throughout with language and provisions, e.g., poll taxes, that reflect the racist intent of those who originally wrote it. While much of this language has been declared illegal and voided by twentieth century court rulings, it is still in the document and has been pointed to by other states when competing with Alabama for economic growth.

The need for a revision to Alabama’s Constitution has been long recognized and was confirmed by the Legislature in 2019 when it unanimously agreed to give the people of Alabama an opportunity to approve an amendment for constitutional reform, which they did. Since then, the Legislature worked with the non-partisan Legislative Services Agency to create a draft that cleans up and consolidates the document and puts it in a logical structure that is easier for all to understand. Earlier this year the Legislature unanimously supported and Governor Kay Ivey approved the revised document. This document, if approved by the voters, will be called the Alabama Constitution of 2022. It will not make any substantive changes to how government functions in Alabama. However, it will remove all duplication, eliminate all now-illegal racist language and provisions, arrange all local amendments by county of application, and make the Constitution far more easily understood by all citizens of the state.

The proposed updates can be found on the website of the Secretary of State at www.sos.state.al.us and LSA at www.legislature.state.al.us/lsa

Wayne Flynt, Professor Emeritus, History, Auburn University says “The unanimous support of our state lawmakers, on both sides of the aisle has been a key factor in paving the way for our state’s much-needed constitutional updates. These steps will bring clarity to the document, making it easier for all of us to understand. Our state’s economic development leaders also believe the revisions will help the state attract more business opportunities.”

State Representative Merika Coleman (D), who sponsored the original legislation, said that adopting the Constitution of 2022 would send “a message out about who we are. It is important for us to let folks know we are a 21st century Alabama, that we’re not the same Alabama of 1901 that didn’t want Black and white folks to get married, that didn’t think that Black and white children should go to school together.”

House Speaker Mac McCutcheon (R) said “For several years, we’ve been working on cleaning up the Constitution and the wording in it, and this will move us forward with helping to accomplish that. There is some racist terminology in there and this is going to address all of that.”

The wording on the ballot for the ratification of the revised Alabama constitution will read: “Proposing adoption of the Constitution of Alabama of 2022, which is a recompilation of the Constitution of Alabama of 1901, prepared in accordance with Amendment 951, arranging the constitution in proper articles, parts and sections, removing racist language, deleting duplicated and repealed provisions, consolidating provisions regarding economic development, arranging all local amendments by county of application and making no other changes.”

On November 8 vote “Yes” on the adoption of the Constitution of Alabama of 2022.

Alabama’s 1901 Constitution was aimed at keeping blacks and poor whites from voting and achieved the framers’ intent.

A proposed Alabama Constitution of 2022 appears to be on its way to voters for ratification in this fall’s general election.

Today, the Alabama Senate passed a resolution to put the question on the ballot in November. The vote was 23-0. That follows approval by the House on a 94-0 vote last week.

Gov. Kay Ivey’s signature is the next step.

“Governor Ivey looks forward to signing the resolution to give the people of Alabama the opportunity to vote on it in November,” Gina Maiola, communications director for the governor, said in an email.

The proposed new constitution is a reorganized version of the Constitution of 1901, with racist, repealed, and duplicative sections removed.

The project, supported by Democrats and Republicans in the Legislature, has been in the works for three years. In 2019, Rep. Merika Coleman, D-Pleasant Grove, sponsored legislation proposing to voters an amendment to authorize recompiling the constitution, with changes limited to five categories:

By a two-to-one margin, voters approved Coleman’s amendment in November 2020 to authorize the recompilation.

Since then, the Legislative Services Agency, with guidance from a 10-member committee and comments from the public, has compiled the new constitution. It can be found on the agency’s website, along with more information about how the process has worked.

The goal was to make the massive Alabama Constitution of 1901, which has been amended 977 times, easier to read, use, and understand, as well as eliminating sections intended to preserve racial segregation and white supremacy that predated the civil rights movement.

Coleman has credited the organization Alabama Citizens for Constitutional Reform, a nonprofit group started in 2000, with helping to spearhead the legislation.

Read more: Plan to take racist, outdated language from Alabama’s Constitution moves ahead

Panel hones in on racist sections in Alabama Constitution

Three sections were changed to repeal racist language.

Section 32, which prohibits slavery and involuntary servitude, carries an exception, allowing involuntary servitude “for the punishment of crime, of which the party shall have been duly convicted.”

That exception was deleted from the revised constitution.

The authorization of involuntary servitude for punishment of a crime was used to force many Blacks into labor after the end of slavery.

African Americans made up more than 90% of convicts forced to work at farms, lumber yards and coal mines under Alabama’s convict-lease system, according to the Encyclopedia of Alabama.

Section 259 is a relic of the poll taxes used to disenfranchise Black voters. It says, “All poll taxes collected in this state shall be applied to the support and furtherance of education in the respective counties where collected.” That is deleted from the revised constitution.

Poll taxes were outlawed by the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1964.

Section 256 is a statement of policy on public education. It initially called for “separate schools for white and colored children.”

Alabama revised that with Amendment 111 in 1956, a period when the state tried to resist following the Brown v. Board of Education decision that outlawed segregated schools. The amendment says the state’s policy is to foster and promote public education but that the Legislature has the authority “to require or impose conditions or procedures deemed necessary to the preservation of peace and order.”

The revised constitution deletes that italicized language.

Also deleted from Section 256: “To avoid confusion and disorder and to promote effective and economical planning for education, the legislature may authorize the parents or guardians of minors, who desire that such minors shall attend schools provided for their own race, to make election to that end, such election to be effective for such period and to such extent as the legislature may provide.”

Parts of the 1901 Constitution that have long been invalidated by courts or annulled by other amendments, which remain in the document now, are deleted from the recompiled version. Examples are the requirement for “separate schools for white and colored children,” as well as Section 102, which says, “The legislature shall never pass any law to authorize or legalize any marriage between any white person and a negro, or descendant of a negro.”

Legislation currently being discussed in the Alabama House of Representatives are HJR52 and HB319.

HJR52 is a resolution that will allow the Constitution’s recompilation, done by Legislative Services Agency and citizen advisors, to take effect.

That recompilation, authorized by a constitutional amendment approved by voters in 2020, eliminates racist language as well as duplication and words previously repealed. It does not add or change any other legal wording. If passed, HJR52 will go to voters in November.

HB319 merely allows the Code Commissioner (after HJR52 is passed) to renumber sections changed by the recompilation and carry over the descriptions of change from the previous Constitution. HB319 will also go to voters in November.

Here are copies of HJR52 and HB319

1 HJR52

2 215715-2

3 By Representatives Coleman, McCutcheon, Daniels, Garrett,

4 Robbins and Drummond

5 RFD: Rules

6 First Read: 09-FEB-22

Page 0

1 215715-2:n:02/08/2022:PMG/bm LSA2021-2713R1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8 ADOPTING THE PROPOSED CONSTITUTION OF ALABAMA OF

9 2022 AND PROPOSING RATIFICATION AT THE 2022 GENERAL ELECTION.

10

11 WHEREAS, Amendment 951 to the Constitution of

12 Alabama of 1901, ratified on November 3, 2020, requires the

13 Director of the Legislative Services Agency, during the 2022

14 Regular Session, to propose a draft Constitution of Alabama of

15 2022, which is a recompilation of the Constitution of Alabama

16 of 1901, arranging the constitution in proper articles, parts,

17 and sections, removing all racist language, deleting

18 duplicative and repealed provisions, consolidating provisions

19 regarding economic development, arranging all local amendments

20 by county of application, and making no other changes; and

21 WHEREAS, the Joint Interim Legislative Committee on

22 the Recompilation of the Constitution was created by Act

23 2021-523 to assist in the revision of the Constitution of

24 Alabama of 1901, receive input from the public regarding the

25 revision, and collaborate with the Director of the Legislative

26 Services Agency in the preparation of a proposed draft of the

27 constitution, as required by Amendment 951; and

Page 1

1 WHEREAS, the Joint Interim Legislative Committee on

2 the Recompilation of the Constitution was comprised of

3 Representative Merika Coleman, Chair, Senator Arthur Orr, Vice

4 Chair, Representative Danny Garrett, Senator Sam Givhan,

5 Representative Ben Robbins, Senator Rodger Smitherman, Ms.

6 Anita Archie, Mr. Greg Butrus, Mr. Stan Gregory, and Mr. Al

7 Vance; and

8 WHEREAS, during 2021, the Joint Interim Legislative

9 Committee on the Recompilation of the Constitution held

10 numerous public meetings to discuss the proposed recompilation

11 of the constitution, received input from the public, and

12 collaborated with the Director of the Legislative Services

13 Agency in the preparation of the proposed draft recompilation

14 of the constitution; at its November 3, 2021, meeting, the

15 committee unanimously voted to adopt the draft recommended by

16 the director; and

17 WHEREAS, the proposed Constitution of Alabama of

18 2022 uses as its base the statutory recompilation of the

19 Alabama Constitution of 1901, authorized by Act 2003-312 and

20 appearing as Volumes 1 and 2 of the Code of Alabama 1975 for

21 over 15 years; and

22 WHEREAS, the final draft of the proposed

23 Constitution of Alabama of 2022 is available for review on the

24 website of the Legislature and the Secretary of State and has

25 been made available to any state agency, county, or

26 municipality for posting in accordance with Amendment 951; now

27 therefore,

Page 2

1 BE IT RESOLVED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF ALABAMA, BOTH

2 HOUSES THEREOF CONCURRING, That

3 (a) The proposed Constitution of Alabama of 2022,

4 prepared by the Director of the Legislative Services Agency,

5 with advice and recommendations from the Joint Interim

6 Legislative Committee on the Recompilation of the

7 Constitution, as well as members of the public through that

8 process, complies with Amendment 951 to the Constitution of

9 Alabama of 1901, and only arranges the Constitution of Alabama

10 of 1901 into proper articles, parts, and sections, removes

11 racist language, deletes duplicative and repealed provisions,

12 consolidates provisions regarding economic development,

13 arranges all local amendments to the constitution by county of

14 application, and makes no other changes.

15 (b) In accordance with Amendment 951 to the

16 Constitution of Alabama of 1901, the draft Constitution of

17 Alabama of 2022, proposed by the Director of the Legislative

18 Services Agency with advice and recommendations from the Joint

19 Interim Legislative Committee on the Recompilation of the

20 Constitution, is hereby adopted and incorporated by reference

21 herein.

22 (c) The proposed Constitution of Alabama of 2022

23 shall be submitted to the qualified electors of this state for

24 ratification pursuant to Amendment 714 of the Constitution of

25 Alabama of 1901, now appearing as Section 286.01 of the

26 Official Recompilation of the Constitution of Alabama of 1901,

27 as amended, and Amendment 951 to the Constitution of Alabama

Page 3

1 of 1901, except that the text of the proposed Constitution of

2 Alabama of 2022 shall be published on the public website of

3 the Secretary of State and the website of the Legislature and

4 shall be made available, without cost, to any agency of the

5 state or a municipality or county in the state that operates a

6 public access website for publication on the website at their

7 request.

8 (d) Upon ratification of the proposed Constitution

9 of Alabama of 2022 by a majority of the qualified electors of

10 this state voting on the question of the ratification in

11 accordance with Amendment 951, this resolution, and the

12 election laws of this state, the Constitution of Alabama of

13 2022 shall succeed the Constitution of Alabama of 1901, as the

14 supreme law of this state in accordance with Amendment 951.

15 (e) An election upon the proposed Constitution of

16 Alabama of 2022 shall be held at the 2022 general election, at

17 which time the officers of the general election shall open a

18 poll for the vote of the qualified electors upon the

19 ratification of the proposed constitution. The Secretary of

20 State shall place the question of ratification on the election

21 ballot and shall set forth the following description:

22 “Proposing adoption of the Constitution of Alabama

23 of 2022, which is a recompilation of the Constitution of

24 Alabama of 1901, prepared in accordance with Amendment 951,

25 arranging the constitution in proper articles, parts, and

26 sections, removing racist language, deleting duplicated and

27 repealed provisions, consolidating provisions regarding

Page 4

1 economic development, arranging all local amendments by county

2 of application, and making no other changes.”

3 This description shall be followed by the following

4 language:

5 “Yes ( ) No ( ).”

PAGE 5

1 HB319

2 216074-1

3 By Representatives Coleman, McCutcheon, Daniels, Garrett,

4 Robbins and Drummond (Constitutional Amendment)

5 RFD: Constitution, Campaigns and Elections

6 First Read: 09-FEB-22

Page 0

1 216074-1:n:01/31/2022:KMS/cr LSA2021-2712

2

3

4

5

6

7

8 SYNOPSIS: This bill would propose an amendment to the

9 Constitution of Alabama of 1901, to authorize the

10 Code Commissioner, contingent upon the ratification

11 of the Constitution of Alabama of 2022, to renumber

12 and place ratified constitutional amendments, based

13 on a logical sequence and the particular subject or

14 topic of the amendment, and to provide for the

15 transfer of existing annotations to any section of

16 the Constitution of Alabama of 1901, to the section

17 as it is numbered or renumbered in the Constitution

18 of Alabama of 2022.

19

20 A BILL

21 TO BE ENTITLED

22 AN ACT

23

24 To propose an amendment to the Constitution of

25 Alabama of 1901, to authorize the Code Commissioner,

26 contingent upon the ratification of an official Constitution

27 of Alabama of 2022, to renumber and place ratified

Page 1

1 constitutional amendments, based on a logical sequence and the

2 particular subject or topic of the amendment, and to provide

3 for the transfer of existing annotations to any section of the

4 Constitution of Alabama of 1901, to the section as it is

5 numbered or renumbered in the Constitution of Alabama of 2022.

6 BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF ALABAMA:

7 Section 1. The following amendment to the

8 Constitution of Alabama of 1901, as amended, is proposed and

9 shall become valid as a part thereof when approved by a

10 majority of the qualified electors voting thereon and in

11 accordance with Sections 284, 285, and 287 of the Constitution

12 of Alabama of 1901, as amended:

13 PROPOSED AMENDMENT

14 Contingent upon the ratification of the Constitution

15 of Alabama of 2022:

16 (a) The Code Commissioner shall number and place any

17 constitutional amendment ratified on the date of ratification

18 of this amendment as appropriate in the Constitution of

19 Alabama of 2022, based upon a logical sequence and the

20 particular subject or topic of the amendment.

21 (b)(1) Any judicial decision interpreting a

22 provision of the Alabama Constitution of 1901, shall remain

23 valid as to the appropriate provision in the Constitution of

24 Alabama of 2022, that has not been substantively changed by

25 the Constitution of Alabama of 2022. Any case annotation to

26 any section of the Constitution of Alabama of 1901, compiled

27 and published prior to the ratification of this amendment

Page 2

1 shall apply to the section as it is numbered or renumbered in

2 the Constitution of Alabama of 2022, as authorized by

3 Amendment 951.

4 (2) The Code Commissioner shall instruct the

5 publisher of the Official Recompilation of the Constitution of

6 Alabama of 1901, to transfer, organize, and otherwise arrange

7 annotations to the same or renumbered sections of the

8 Constitution of Alabama of 2022, except to the extent

9 substantively changed.

10 Section 2. An election upon the proposed amendment

11 shall be held in accordance with Sections 284 and 285 of the

12 Constitution of Alabama of 1901, now appearing as Sections 284

13 and 285 of the Official Recompilation of the Constitution of

14 Alabama of 1901, as amended, and the election laws of this

15 state.

16 Section 3. The appropriate election official shall

17 assign a ballot number for the proposed constitutional

18 amendment on the election ballot and shall set forth the

19 following description of the substance or subject matter of

20 the proposed constitutional amendment:

21 “Proposing an amendment to the Constitution of

22 Alabama of 1901, to authorize the Code Commissioner,

23 contingent upon the ratification of an official Constitution

24 of Alabama of 2022, to renumber and place constitutional

25 amendments ratified before or on the same day as the

26 Constitution of Alabama of 2022, based on a logical sequence

27 and the particular subject or topic of the amendment, and to

Page 3

1 provide for the transfer of existing annotations to any

2 section of the Constitution of Alabama of 1901, to the section

3 as it is numbered or renumbered in the Constitution of Alabama

4 of 2022.

5 “Proposed by Act ________.”

6 This description shall be followed by the following

7 language:

8 “Yes ( ) No ( ).”

Page 4

A committee studying racism in the Alabama Constitution gave tacit approval Wednesday to a plan to remove language on school segregation, poll taxes, and involuntary servitude.

The Committee on the Recompilation of the Constitution did not take a formal vote on the proposal from Othni Lathram, the director of the Legislative Services Agency. But no member of the committee raised objections to it.

“I’m reading today’s action as that the committee is generally comfortable with the direction on racist language,” Lathram said.

Lathram’s proposal would:

Committee members did not raise objections to the plan. A formal vote on the proposal should take place within the next few weeks.

“I just want to make sure that we’re all on the same page, because at the end of the day, I want to say that this is a document that was bipartisan,” said Rep. Merika Coleman, D-Pleasant Grove, who chairs the committee and sponsored the 2020 constitutional amendment that led to its formation. “Really nonpartisan, because it shouldn’t be partisan at all.”

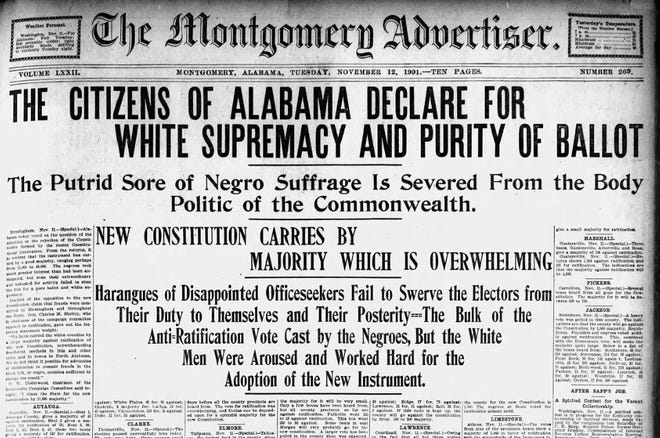

The framers of Alabama’s 1901 constitution — still the state’s governing document — designed it to disenfranchise Black Alabamians and poor whites, and waged a racist campaign to see it enacted.

“And what is it we want to do?” John Knox, the president of the convention, told the delegates to the convention in May 1901. “Why, it is within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution, to establish white supremacy in this state.”

The constitutional amendment setting up the commission, sponsored by Coleman, had bipartisan support and got the approval of about two-thirds of Alabama voters in 2020.

Some committee members who supported the changes expressed concerns about the potential for future litigation. Stan Gregory, an attorney serving on the committee, said that if the mandate of the committee was to address racist language, addressing issues like the poll tax — which, on its face, was applied to all — could open a door to litigation.

“It’s not much,” said Gregory, who said he supported the removal of the poll tax language. “I think that it’s defensible. I just point that out — that’s something that worries me.”

Lathram said he understood the concern but said the applications of the provisions throughout state history were racist. He said h believed the proposal considered in its “totality” would withstand legal challenges.

The 1956 amendment asserts that there is not “any right to education or training at public expense.” That language would remain in the document under the plan.

The Legislature will take up the committee’s recommendations when they return in January, in the form of a constitutional amendment. If the amendment passes, it will go to voters in November 2022.

Federal laws and court rulings have nullified most of the racist provisions that remain within the state constitution. But Coleman said the changes would send a message.

“Our state constitution is reflective of who we are,” she said after the meeting. “Those racist provisions in that constitution, those outdated provisions — we hope that’s not who we are, and we definitely know we’re not a 1901 Alabama, and we need to reflect that in the document.”

Contact Montgomery Advertiser reporter Brian Lyman at 334-240-0185 or [email protected].

Many outdated provisions have long since been invalidated, but the language that was specifically intended to enshrine white supremacy has remained.

The last time Alabama politicians rewrote their state Constitution, back in 1901, their aspirations were explicitly racist: “to establish white supremacy in this state.”

“The new Constitution eliminates the ignorant Negro vote and places the control of our government where God Almighty intended it should be — with the Anglo-Saxon race,” John Knox, the president of the constitutional convention, said in a speech encouraging voters to ratify the document that year.

One hundred twenty years later, the Jim Crow-era laws that disenfranchised Black voters and enforced segregation across Alabama are gone, but the offensive language written into the state Constitution remains. Now, as communities across the South reconsider racist symbols and statues, activists in Alabama who have labored for 20 years to convince voters that rewriting their Constitution is important — and long overdue — see an opportunity to get it done.

“I am tired of being treated as a second-class citizen, and terms like ‘colored’ that are throughout the Constitution play a part in that feeling,” said Marva Douglas, an actress and retired teacher who first joined Alabama Citizens for Constitutional Reform in the early 2000s.

Efforts to rewrite the state constitution failed twice before. But last fall, voters — jolted partly by racial justice protests across the country — gave a green light. This month, a committee of lawmakers and lay people began the process of redrafting; their work will go before the voters next year to be ratified before the new constitution can take effect.

The redrafting campaign may not be as dramatic as efforts elsewhere to reform the criminal justice system or tear down Confederate monuments, but advocates argue that addressing racist language is a critical part of reckoning with the past.

“It’s not an either-or, it’s a continuum,” said Paul Farber, the director of Monument Lab, a Philadelphia-based public art and research studio dedicated to examining how history is told in the public landscape. “Part of the work is to understand how symbols carry weight and how they are connected to systems that structure public institutions and spaces and opportunity.”

Shay Farley, regional policy director for the Southern Poverty Law Center, describes the effort as a way for the state to signal its collective rejection of white supremacy. “We must remove the lingering vestiges of racial segregation and legalized oppression of Alabama’s Black residents,” she wrote in a letter endorsing the constitution project.

The effort will start by extracting passages like Section 256, which still says that “separate schools shall be provided for white and colored children, and no child of either race shall be permitted to attend a school of the other race,”

The state Constitution also includes a ban on interracial marriage, though the U.S. Supreme Court ruled such marriages to be fully legal in all states in 1967. “The Legislature shall never pass any law to authorize or legalize any marriage between any white person and a Negro, or descendant of a negro,” the state Constitution still says.

And it includes descriptions of former voting requirements that were generally used to disenfranchise Black residents, including literacy tests and poll taxes. (The Constitution, written before women won the right to vote nationally, also includes language restricting voting to men.)

Two previous failed efforts to remove the section on school segregation — which was outlawed nationally by the Supreme Court in its 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision — were complicated by a related debate over a 1956 state amendment that said Alabama did not recognize any right to a publicly funded education whatsoever, language that was aimed at thwarting the ruling on desegregation.

When advocates tried to get rid of both passages at once in 2004, opponents argued that the result would be higher taxes to increase school funding. Then in 2012, an effort to get rid of the segregation language without touching the public funding language drew opposition from school advocates — ultimately leaving the Constitution as it was.

To Representative Merika Coleman, a Democrat and the assistant minority leader in the Alabama House of Representatives, getting rid of outdated and racist language is an opportunity to improve the state’s reputation.

Last summer, she recalled, just when many residents were participating in ceremonies honoring the life of the civil rights leader John Lewis, one of her State House colleagues participated in a celebration of the birthday of Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate general and the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

“That story made the national news,” she said. “All of the negative images that come from here make the news.”

Ms. Coleman wants the reputation of Alabama as intolerant and racist to change. “Collectively, we are not those folks that were celebrating the birthday of the K.K.K.,” she said. “That’s not who we are.”

She also worries about the impact of the current Constitution’s effect on schoolchildren.

“If your image, based on what we’re talking specifically about the Constitution, is that you are not worthy enough to vote, you are not worthy enough to marry who you love, you are not worthy enough to have the best education possible, what does that say about who you are?” she asked. “And what about the superiority complex that it creates in non-people of color?”

The project, if successful, will also allow the state to streamline the entire document — the longest state Constitution in the country — making it easier to navigate and understand and removing other sorts of outdated provisions.

Representative Coleman, who sponsored the constitutional amendment that set the redrafting in motion and now chairs the committee considering changes to the charter, also sees the removal of racist language as an entry point to conversations about current-day policies that disproportionately affect Black residents. She points to a passage on “involuntary servitude,” which is illegal except in the case of people convicted of crimes. The practice, she said, has disproportionately affected Black Americans, who for decades have been sentenced to toil on prison farms and to do other forms of prison labor.

“We’re having real-deal conversations where people may not have been having those conversations before, conversations we should have had a long time ago,” Ms. Coleman said.

Tariro Mzezewa is a national correspondent covering the American South. @tariro

An advisory panel for a voter-approved effort to make changes to the 120-year-old Alabama Constitution is studying three sections that had racist language or racist intent.

The Committee on the Recompilation of the Constitution held a public hearing at the State House this morning. The committee did not make recommendations because it is still receiving public comments.

Voters approved a constitutional amendment authorizing the recompilation project by a 2-to-1 margin in November 2020. In May, the Legislature passed a resolution setting up the 10-member recompilation committee.

The recompilation committee, which includes six lawmakers and four others, will advise Lathram, whose draft will go to the Legislature next year. If approved by three-fifths of representatives and senators, it would go on the ballot for voters in November 2022.

This morning, Lathram made a presentation to the committee and distributed a memo about sections of the constitution that have been called into question as racist or potentially racist.

The authorization of involuntary servitude for punishment of a crime could qualify as a racist provision because it was used to force many Blacks back into labor, including the seasonal agricultural work for which slaves were no longer available, Lathram said.

Lathram said about 19 other states had similar language on involuntary servitude in their constitutions. He said voters in Colorado, Nebraska, and Utah voted to repeal the language during the last three years, and voters in Tennessee will consider that next year.

Lathram noted that almost identical language allowing involuntary servitude as a punishment for crime is included in the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery.

Some of the commenters questioned the value of the recompilation project, Lathram said, suggesting that it was a waste of time to revisit outdated, nullified laws. Lathram said he did not agree with that.

Rep. Merika Coleman, D-Pleasant Grove, who sponsored the constitutional amendment starting the process and who chairs the recompilation committee, said the recompilation project is important.

“On the economic development side, we also want folks to know we’re open for business. We want people to come to the state of Alabama, spend your tax dollars, and that we again are a state that is this 21st century state, all kinds of different people, all kinds of different cultures, and we do not reflect what was in that 1901 constitution.”

“I think words matter,” Garrett said. “And I think we need to just clean the constitution up, make it a document that is relevant today. We have a history that we’re trying to address. And we’re trying to move from the past to the future. And I think this is an obstacle in many ways.

“I think it’s important that as a state with our history that we acknowledge where we want to go. And where we want to go is not where we’ve been necessarily.”

Section 259 says revenue from poll taxes goes to support public schools in counties where they are collected. The section is inoperative because Alabama no longer imposes poll taxes, which effectively disenfranchised many Blacks and poor white voters.

Sen. Sam Givhan, R-Huntsville, a committee member, made a motion today for the committee to vote to recommend removal of Section 259. But the committee decided to postpone voting on any recommendations because public comments are still coming in.

That segregation requirement became unconstitutional after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1954.

That became an issue in 2004, when a proposed amendment would have repealed the segregated schools requirement and poll tax language, as well as the part of Amendment 111 saying there was no right to a publicly funded education.

In 2012, a similar amendment would have repealed the school segregation and poll tax language but would not have touched the language from Amendment 111 that there was no right to a publicly funded education. That drew opposition from the Alabama Education Association and others who argued for stripping the language on no right to a publicly funded education. Voters rejected the amendment by about a 60-40 percent margin, again allowing the invalidated segregation clause to remain in the constitution.

The next Constitution Recompilation Committee meeting will be Thursday September 2nd at 10:00 in room 200 of the State House, 200 South Union Street in Montgomery.

The subject to be discussed will be Racist Language.

The public is invited to attend and to submit questions and concerns to [email protected] or to call 334-261-0690.

The meeting on the 2nd can also be watched on www.legislature.state.al.us under Resources and then Media. It is listed as House Committee Room 200.

All information about the meetings is available on lsa.state.al.us under news.

Legislators on Tuesday took the first formal steps in a process that could eliminate racist language in the Alabama Constitution — and, maybe, make it more readable.

The Committee on the Recompilation of the Constitution met for the first time Tuesday morning to hear a presentation on ways to reorganize local amendments in the state’s government document. The committee, which will carry out the decrees of a constitutional amendment approved by voters last November, should take up racist language at its first meeting in September.

“It’s for citizens to know what laws apply to them,” said Othni Lathram, director of the Legislative Services Agency, in an interview after the meeting. “750-plus of the 970-some odd amendments apply in only one county or one city. The vast majority of amendments we talk about are local amendments.”

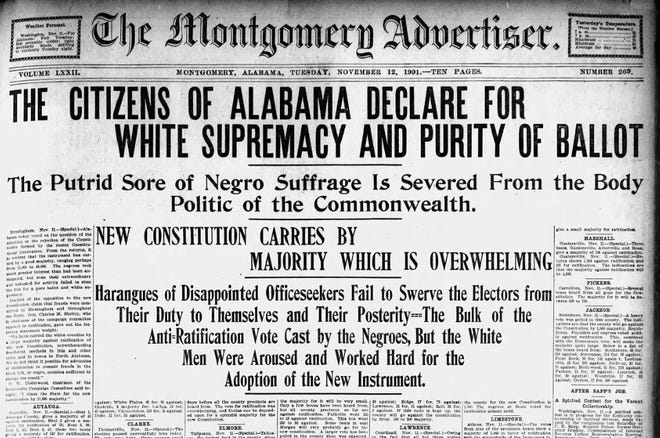

Alabama’s 1901 Constitution disenfranchised Black Alabamians and poor whites, and supporters made explicitly racists appeals to white voters to enact it. The day the Constitution received approval — likely through massive fraud in the Black Belt — the Montgomery Advertiser announced that “The Citizens of Alabama Declare For White Supremacy and Purity of Ballot.”

A 2004 proposal to remove the language would also have jettisoned Amendment 111. The proposal drew the opposition of former Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore and others who claimed that it would jeopardize private schools and lead to tax increases. The amendment failed to pass by about 2,000 votes, out of 1.4 million cast.

A 2012 amendment to remove the racist language would have retained Amendment 111. The Alabama Education Association and Black legislators campaigned against the proposal, saying it could complicate efforts to increase public school funding in Alabama. Almost 61% of voters that year voted no on the proposal.

Last year’s amendment passed with about 67% of the vote. The committee will submit a proposed amendment to the Legislature for consideration next year that would remove racist language and reorganize the Constitution. But Nancy Ekburg with Alabama Citizens for Constitutional Reform, said at the meeting that the committee would not rewrite the state’s governing document.

“We don’t have a mandate to rewrite the Constitution,” she said. “I want to make sure people understand that. We are only recompiling the document.”

Rep. Merika Coleman, D-Pleasant Grove, who sponsored last November’s amendment and chaired Tuesday’s meeting , has said removal of the language would be a symbolic act that could show Alabama trying to move on from its racist past.

Lathram said he plans to make presentations on the racist language within the state’s governing document at the scheduled Sept. 2 meeting.

The committee will also look at amendments focused on economic development.

If the Legislature approves the changes proposed by the committee, the measure will go to voters for approval in November 2022.

Contact Montgomery Advertiser reporter Brian Lyman at 334-240-0185 or [email protected].